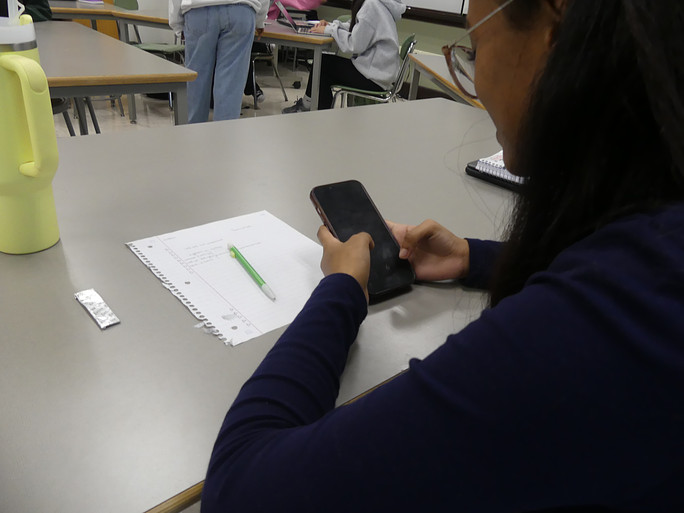

In a world with such an embedded reliance on technology, it’s not difficult to believe that phone use has permeated classrooms, but the extent to which it has disrupted learning has been shocking. High schools worldwide are finding that, increasingly, what was once a lively environment of fostering curiosity and making life-long memories is now one of social media, online shopping, and silence.

Jennifer Clapp, a long-time English teacher who teaches multiple AP courses, reflected on her classroom environment in prior years, stating, “The English department all noticed, post-pandemic, it’s been difficult to get that community feeling.” She claimed that classes “used to have a lot more life.”

“I think it’s a problem for everyone,” affirmed Physics teacher Julie Grillon, “you’re missing out on life in general…it’s a society problem. It’s made the school space less enjoyable for me because there isn’t as much connection between students.”

Over the summer, the English and World Language departments concluded that the best course of action to restore community and focus would be to enact a stricter phone policy. The policy outlines the expectation that all students must place their phones in a designated area at the beginning of all English and World Language classes. Specific implementation varies by class, with many teachers opting for slotted wooden boxes or “cell phone trees,” which are numbered pocket holders that hang on classroom doors.

However, one thing is universal: “Cell phones are not to be seen, used, or in possession of the students during classes,” states English department leader Yahaira Marquez. “As a department…we can’t change the school policy, but we can do something to help on a smaller scale.”

Teachers’ reaction to the new policy has been overwhelmingly positive. Many faculty members are witnessing enhanced student focus without the distraction of cell phones. “Focusing on your work…is so much better without the constant barrage of notifications and alerts,” stated Clapp. “Last year, I didn’t make people put it away, and I was always having to address it…this has been much better [with] it not being a distraction.”

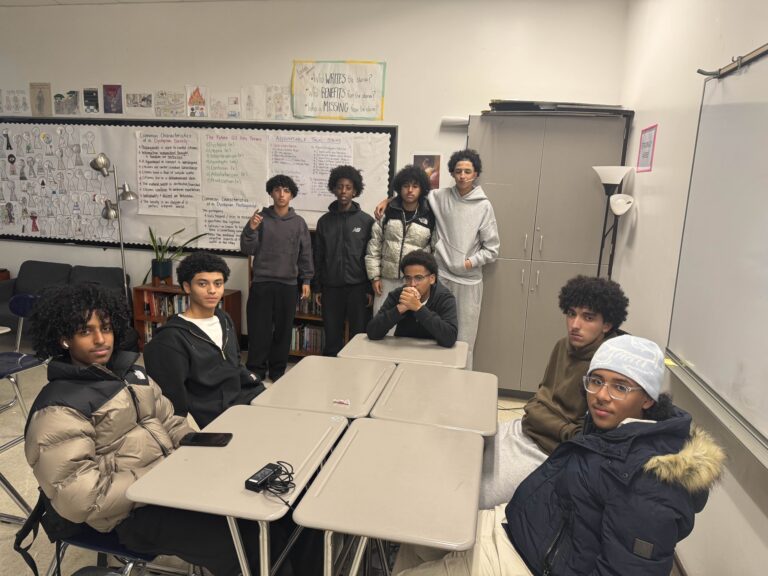

Additionally, many are finding that student engagement has drastically improved without the disruptive influence of phones. Lucia Musilli, an English teacher and former librarian at MHS, observes that “students are more present.” According to Clapp, “The lack of distractions has really improved classroom interactions.”

Ariana Messana, an English and Theater teacher entering her 2nd year at Malden High, reflects on how it’s “A chance for teachers and students alike to unplug.”

Clapp even finds that she’d like the policy to extend outside of the classroom environment into other parts of the school day, “I’ve thought about [implementing the policy] with my morning meeting group…they just don’t talk to each other.” She understands, however, that the pushback for this would be more problematic and that the administration is likely far from implementing such a policy.

Though the policy remains contained within English and World Language classes, other departments are witnessing the change in atmosphere. Grillon acknowledges that she, “has had better interactions with students this year than last year.”

Student reception of the new policy has also been primarily positive. “When I’m constantly working with other people, it’s nice not to have that distraction,” Senior Addison McWayne reflected. “When we don’t have our cellphones on us, we can be more creative.”

While most high schools are now recognizing the harmful effects of cell phone use in schools, 45 Massachusetts high schools are implementing a stricter approach this year: Yondr pouches. In this scenario, each student is assigned a small pouch where they must place their phone. Their phone is inaccessible for the day, and students can only receive it once it is over.

“I think a lot of teachers would like a school-wide policy,” Marquez admits, “maybe not next year, but down the line.”

Despite this, faculty and students are relatively unified around the idea that this approach would not only be impractical to implement but, for the most part, harmful in more ways than one.

“I don’t think we have the infrastructure or the manpower to implement the Yondr pouch,” said Musilli. “I also disagree with it as a parent of a high school student. There are certain times when my kid might contact me, or I need to contact them.”

“If I didn’t have access to it all day long,” stated McWayne, “it would be more difficult for me to learn in general.”

Overall, this policy arrives at a crucial moment when the harmful effects of phone use can no longer be overlooked. While we’ve strayed from this principle in recent years, this new strategy invites the possibility of an environment where education and communication once again become the central focus of every classroom—one where students exit class with newfound skills and memories rather than new Instagram followers. As Clapp puts it, “learning is always the priority.”